The Internet as a True Lockean State of Nature

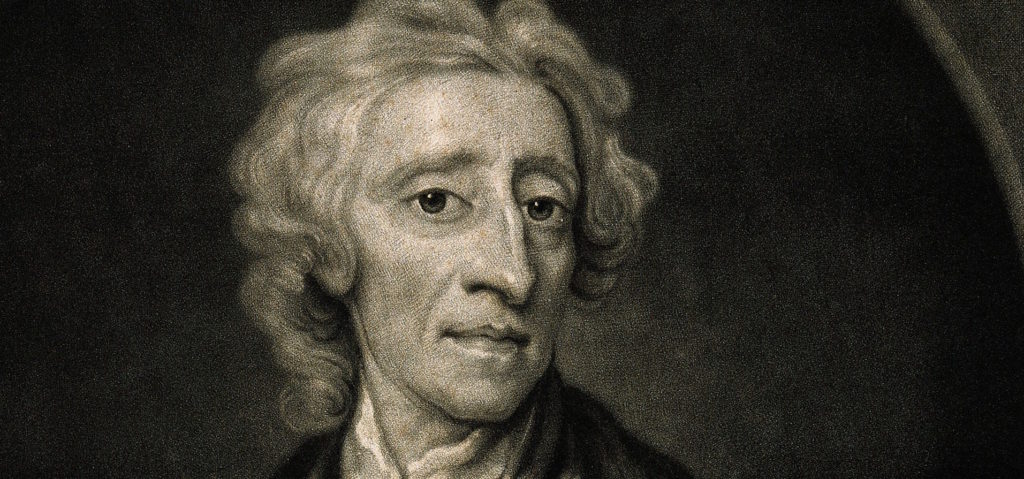

John Locke (1632-1704) was a pivotal British philosopher who lived in a time of tumultuous change. Not only was he exiled from England twice, but he was probably responsible more than anyone else for giving voice to the ideas that led the civilized world away from monarchic systems with kings and queens and rites of succession to democracy. He was a contemporary of Gottfried Leibniz and was a friend of Isaac Newton. Locke’s political philosophy was hugely influential with the drafters of the constitution of the United States and with every other democratic government in the civilized world. His ideas about the shape of human society in the absence of organized government are almost eerily prescient of the current state of the web.

State of Nature

Locke starts his treatise on civil government with an idea that he calls the “state of nature.” What Locke means by this is not that we started from some kind of primitive culture, like a society of savages. In fact, he hijacks the term from peers who actually do mean exactly that, and recasts the idea to his own purposes. To quote Locke,

‘Men living together according to reason, without a common superior on earth with authority to judge between them, is properly the state of nature.’

So, if you have people living in a community in a reasonable and peaceful way, with no common authority or government to rule them, that is what Locke would call a “state of nature.”

In Locke’s day, indeed up until very recent times, the idea that an ungoverned rational community was the seedbed for all forms of government has been open to criticism, in that it was a completely theoretical construct which never really existed. However, we have an almost pure manifestation of a society in a state of nature on the grandest of scales in the internet. On the internet there really is no governance at all. The protocols set out by the w3c (the organization that sets standards for things like HTML) are no more than the suggested bottom-line requirements to make the plumbing work. Even these standards are not enforced in any way, they are adhered to only loosely and largely as a result of men living together according to reason. Not only is there no governing body to draft laws as concern digital society, no judicial body to apply such laws, no executive body to make sure the laws are enforced, but when outside government bodies attempt to bring such things to bear upon human conduct on the internet, they fail terribly. The internet really does function outside of national boundaries and seems to easily wiggle out of and around any kind control by the laws and efforts of particular sovereign nations.

Pirate Bay

For example, consider the web site thepiratebay.org (yes it is still in operation!), which as of this writing hosts magnet links, not actual files, from their site. They at one time openly shared correspondence with companies who claimed their site was transgressing their copyright claims, such as the following exchange with Warner Brothers:

(Warner Bros’ letter)

Finally, notwithstanding our use of the required notice form, we

believe that http://thepiratebay.org ‘s activities and services fall

outside the scope of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”).

Our use of this form, as required by law, is meant to facilitate

http://thepiratebay.org ‘s removal of the infringing product listed

above and is not meant to suggest or imply that

http://thepiratebay.org ‘s activities and services are within the

scope of the DMCA.

(Pirate Bay’s Response)

We are well aware of the fact that The Pirate Bay falls outside the

scope of the DMCA – after all, the DMCA is a US-specific legislation,

and TPB is hosted in the land of vikings, reindeers, Aurora Borealis and

cute blonde girls.

In other words, they know full well that their activities lie outside of the scope of many national laws of various countries, and they don’t care! Many judgements have been brought against thepiratebay.org, ordering them to take action to block access to their site from their country. The question is, even if they could figure out a way to do that, does this really have any kind of substantial effect on the whole issue of file sharing, even via thepiratebay.org, even within their own country? Does any nation have the power to force compliance with someone that isn’t even a citizen of their country? No, and even if they did, it would not be difficult to move the affected hosted services elsewhere, and national firewalls can be circumvented. The owners of thepiratebay.org even considered purchasing Sealand, a hosting company located off the shores of England which claims to be its own tiny sovereign nation subject to no national laws. Even during the time when the piratebay.org had ceased to operate, the demand for free content went on and others arose to serve the need. We all begin to get the idea that governments make these kinds of judgments as a futile show of principle, and even they do not really think they can control what people are going to do online. The internet is very much its own society, a society which respects the laws of others very little, and always finds ways to do what it wants. It is indeed a society which remains ungoverned in a state of nature.

The State of War

According to Locke’s thinking, a state of war arises when certain men exercise force in violation of reason and naturally understood justice, and cause reasonable men to take up arms in defense. One of the things that makes it possible for the internet to persist in a state of nature is that it is not probable that actual physical threats will arise; our presence is virtual and far removed. However, digital forms of force do exist, in the form of spam, viruses, spyware, other forms of malware, malicious hacking, so called “phishing” sites, denial of service attacks, the interception of sensitive data such as credit card numbers, blatant piracy, etc. All is not paradise in the anarchic world of the web!

The reason a state of war arises is that some people have in their possession things that other people want. Thus, the natural right to which Locke gave the most attention was the right to private ownership of property. According to Locke, in a state of nature, if a person settles on a piece of land and begins to farm it and work it, his labor earns him the right to own that property. If someone comes and steals the fruit of his labor or forcefully removes him from the land, it is a violation of the reasonable community. The issue of private ownership and the buying, selling and stealing of digital content is one of the most difficult and important issues facing digital society, and will be be dealt with in some detail later on in this series. The point here is that we seem to be following some kind of inevitable path long foreseen by John Locke in which the biggest problem facing a society in a state of nature is the right to private ownership of property.

What Constitutes Digital Theft?

It is fascinating that in normal physical human society, an act of theft generally involves a resource that lies in the possession of the owner, and it must be stolen as an act of violence. Once it is stolen, the resource is gone from the owner’s possession. On the internet, if an item resides on a storage device somewhere, the very act of showing it to someone else causes it to pass into their possession, and the original owner remains in possession of the object as well. Thus it is called into question whether theft is even possible unless the original digital file is destroyed. We have, in effect, created the ideal environment for theft, since the original owner of a digital item could never know when copies are being distributed against his or her will. However, since it is labor which created or transformed the original digital object which, according to Locke, establishes ownership of the object, then it is not that the object is removed from the owner’s possession which is the crime, but that it is taken into possession without recompense or respect for the labor that created the object.

The Genesis of Government

The state of nature exists on the foundation that men are living together according to reason. When a few people arise who do not respect reason, the state of nature is threatened, and the reasonable men band together and begin to help defend one another’s rights and property. This is the incentive for the rise of government. We should not be so naive as to think that digital society remains free of similar incentives. The threats against the internet’s reasonable state of nature do indeed give rise to the desire for some form of governance. Since it exists and operates so clearly outside national boundaries, the incentive will be for this governance to arise over the whole web globally to bring about effectual digital forms of force and control. Thus we have the paradoxical situation in which the very people who most advocate free content are the ones who are driving the forces to end such freedom.

I am not saying that I advocate the idea of a global form of governance over internet society. I am saying that the force of a real incentive is there, it is a real and tangible influence. This is not to say that there are not considerable forces of resistance to some kind of web governance. Indeed, the rest of this series concerns itself with ways to construct systems for the web in which a state of nature can be preserved, in which threats to a reasonable digital community are minimized and rational practices are encouraged by the nature of the system itself. However, if such systems cannot be envisioned and deployed, the incentives for less free-wheeling forms of digital society will rise up against the beautiful anarchy of the web, and the possibility of an enduring society in a true state of nature will be lost. We are not playing games here, these are real and pressing issues with real consequences.

The Internet’s Core Problems are not Technological

We often think that the main bulk of innovation on the web is produced by programmers. Programmers are essential, but the real problems facing us are more fundamental, and we cannot expect independent programmers to magically solve difficult social, ethical, and economic problems by a merely typing out mystic runes. We must come to some basic consensus as to what natural laws concerning the internet’s state of nature we generally agree to. Should we or should we not create systems which enable creators and owners of digital content to establish forms of private ownership of such items in a manner in which they can agree to or deny the sale? The engineering will be far more possible if we settle the question. Many would say that the issue is settled and copyright is dead, but then again there many others who would not agree at all, which means the issue is not settled, and we are in a Lockean sense in a state of war. My solution, which we will delve into in some depth later, is that we enable the owner of the content to deny the sale if they wish, by allowing them to declare their wishes for copying, and create an environment in which those wishes are easily fulfilled. It may seem obvious to say, but the owner owns the item, it should be their place to decide, and if their terms kill the natural distribution of the content in the marketplace, that is their right.

The Beauty of the Internet in a State of Nature

I think that all of us on the web love the state of nature, and in a way we want to keep it the way it is. Practical solutions to problems on the web have to preserve the autonomous nature of digital society and work within the extremely narrow framework of a fragile but working anarchy. If not, we are talking about creating a worldwide digital state with legislative, executive, and judicial powers, which goes very strongly against the general culture of the internet. As we have seen, the imposition of the laws and judgments of individual sovereign nations has proven largely ineffectual. I do not believe the general populace of internet citizenry is ready for the idea of an international governance body for the internet with full-blown legislative, executive, and judicial powers, nor do I personally believe that such a thing is desirable. One of the things that Locke points out is that the state of nature affords a great deal more autonomy and self-determinism than a state under government, and the benefits have to be clear for the governed to consent to give up such freedoms to a central authority. As of now, there is enormous debate about whether most of the threats I will discuss in the rest of this series are even real dangers, much less is there strong incentive to give up the state of nature because of them. Part of the goal is to bring home the consequences of ignoring the reality of the danger these problems represent, and to propose solutions that preserve a state of nature. The world’s nations are similarly not ready to concede the power of a global centralized body of governance over to the internet, even if it would help to honor their own national interests. This would possibly be a major step towards a lessening of the influence of nation-states in non-digital societies, and we can naturally assume extreme levels of resistance as the implications of a global digital government begin to intrude upon the sovereign interests of nations. Some would argue that the era of the nation-state is over and that we live in a global and interconnected economy, but this is not actually true, is it? There are some economic trends which seem to transcend traditional national boundaries, but we are very far from ending the era of the nation-state.

The Internet as a Real State

Nevertheless, the internet as it now exists in a state of nature is a real state; this is a fundamental axiom for the progression of thought in the book. The threats to a reasonable state of nature on the internet are real, and there does exist in various ways, a state of war. When the system ignores the freedoms and interests of certain groups of users, no matter how justified the deprecation of those interests might seem, those users have true incentive to find ways to band together in defense. We will see how the vilification of the interests of one or another groups of users gives incentive to private proprietary splinter networks that operate solely for their own purposes, which further offends others. That is why it is important that the design of the next web acknowledges and embraces the interests of all users in as balanced a way as possible, so that the system itself encourages the continuance of a reasonable state of nature, with the freedom and autonomy that it affords.

The Internet is a Sovereign Nation? No Way!

In case someone misses this, I want to raise my own objection to what is being asserted here. An obvious question at this point is, “Are you saying that the internet is its own sovereign nation? That is balderdash! The internet is only a communication medium, you can’t make such a huge intuitive leap.” Well, what are the things that comprise a sovereign nation? I’ll propose some criteria off the top of my head: they have their own system of governance (even if it happens to be anarchy), they do not obey the laws of other nations, but rather adhere to their own practices, and they have a specific and particular culture and set of ethical values. Of course, as far as the internet is concerned, there can be no notion of geographic or ethnic homogeneity which one would normally associate with a nation, but one could make the case that this is a new paradigm and geography and ethnicity are old and worn out notions anyway. However, I want to clarify what I am saying. I am not saying there is some kind of real nation we might dub “Infotopia” and that we should create a flag and a constitution and draft an internet constitution, I agree that that is lunacy. What I am saying is that the internet does exhibit a lot of the characteristics of a sovereign nation, and that if we look at it in terms of Locke’s ideas about government and society, it explains a good deal of the dynamics we see emerging in terms of a society in a state of nature and in some ways in a Lockean state of war. As someone once said, we ought not make the analogy walk on all fours.

What I really am saying is that the internet, with its components of the web, file sharing services, email, cloud computing services, custom networked applications, all of it, represents a newly emergent true and distinct society. The consequences of the threats to digital society’s state of nature are real threats, with real consequences to real people. There are deep ramifications to our culture and way of life if we do not address these issues with our best thinking. The rules of politics, economics, culture, and technology are deeply intertwined, and must all be reinterpreted to our world-wide digital society.